The use of humour in art has traditionally been consigned to the position of second class citizen, deemed the lesser sillier cousin of high art and used primarily for as a tool for political and social commentary with little merit in its own right. William Hogarth was perhaps the first artist to be taken seriously as an artist and as a humourist. This is perhaps to do with the moral message of his painting, that was in keeping with the grand historical portraiture of the British Academy of the time.

Historically, the medium of painting doesn't lend itself well to humour. It is too reliant on narrative and realism descending into the realm of caricature or cartoon when it attempts to be cheerful. With the expansion of media in contemporary art, humour has found a new place, no longer reliant of funny depictions of people or scenarios, artists are employing ever ingenious means to elicit both a lighthearted chuckle and a deeper philosophical reflections from viewers, giving humour a new found position in contemporary art.

The power of humor in art is when meaning is layered and context destabilizes its superficial funniness to reveal something deeper and more meaningful. Humor can be a useful tool in art: ‘it can destabilize a situation and in a split second, draw the viewer in or allow something else out” – (Adam McEwen British artist based in New York).

Laughter can create a connection between the viewer and the work or the artist, allowing the work to be subversive. Humor can operate as a sign of humanity, in the face of overwhelming or dark situations.

Narrative plays a big role in the use of humor in art. Jokes need a set up, a funny situation or a narrative juxtaposition in order to generate laughs. This leads to a lot of artists who use humor opting for video work, such as Allora and Calzadilla's Returning a Sound (2004-05).

Homar, an activist, rides around Vieques on a moped that Allora & Calzadilla reengineered by a trumpet to the exhaust system. During the ride, every thrust of the throttle or shift in speed alters the instrument's pitch. Allora & Calzadilla have edited out other ambient noise, leaving only the alternately sputtering vibrato and clear, pure sound of the trumpet as a jazzlike soundtrack, a call to action, or perhaps an anthem, as the artists discuss in the interview that follows. Their works counterpose militarism and war with adroit manipulations of sound, music, and spoken word.

Strategically seeking out the sounds of combat as their sonic media, Allora & Calzadilla endeavor to reissue sounds whose meanings have grown far too familiar in an effort to restructure, at the source, those corporeal conformities, always marked in and on the body already, through which violent and potentially devastating action first becomes possible.

Created in 2008 and presented at the Zach Feurer Gallery, New York video artist Tamy Ben-Tor tackles issues pertaining to social customs and gender roles in her video titled Gewald. As evident of her work, Ben-Tor uses child-like story scenarios and songs to awaken social perceptions through her witty portrayals of everyday-life. At first impression, her work seems silly and even irrelevant, but as the video progresses, one may begin to understand the serious subject she addresses and the message conveyed.

At first in Gewald, Ben-Tor dressed in brightly colored folk attire sings how we must be aware of the household “man covered in mud who knows no piece” and the “woman with a cold womb like a frog.” As the video progresses, she advises children to “carve into their hearts” and “turn their eyes away” from the behavioral roles portrayed by these individuals she sings about.

Installations, such as Michael Farrell, or the wall drawings of Dan Periovschi that are also a performance, are mediums more suited to constructing a background or context for the humor to emerge.

Dan Perjovschi is an artist, writer and cartoonist born in 1961 in Sibiu, Romania. Perjovschi has over the past decade created drawings in museum spaces, most recently in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in which he created the drawing during business hours for patrons to see. The drawings present a political commentary in response to current events. Another exhibition of Perjovschi's within a Portuguese bank consists of several comic strip style drawings which address more European issues such as Romania's acceptance to the EU and abortion legalization in Portugal.

While painting or photography can also contain narrative, it needs to deliver its message instantaneously, within one frame restricting the ability to build up layers of meaning or context. Such works tend to go straight for the punch line, delivering their humor in a short sharp kick, such as the studies of perspective by Ai Weiwei.

Humor can also be used to mask the more serious issues, or as a release for dealing with repressed emotions. As Brooklyn artist Chris Doyle says, “If you cant find tremendous humor in the everyday, the sadness becomes overwhelming”. The problem with funny art is that is can often be regarded with suspicion, discouraging a more thoughtful engagement by a viewer. If it is good art it should prompt a second glance, one that looks past the joke to the message being delivered. That is perhaps what separates art that is merely cartoonish, aiming only to inspire a giggle, from art that uses humor as vehicle to discuss a deeper message- Humor that operates as a means to confront other issues rather than an end in itself.

Several themes begin to emerge in the work of artists employing humour.

Political satire has perhaps the most developed historical tradition reaching back before the days of Hogarth. Today artists employ a wider range of materials and references to pack a political punch.

Fergus O'Neill, a Dublin based graphic designer penned the slogan, "Keep Going Sure It's Grand" which he then turned into posters. It's a play on the British, "Keep Calm and Carry On" posters from World War II which were intended to keep the British people calm while they faced potential invasion.

SAVE IRELAND! That’s the objective of graphic designer Fergus O’Neill’s ‘Keep Going Sure It’s Grand’ project. By producing an original edition of 42 billion screen prints, O’Neill is pledging one euro from every sale to the state thus halving our banking crisis debt. He says of the project: “the bid to sell 42 billion of these posters may seem absurd but it can be deemed no more absurd than the outrageous practices and policies that landed us here. There is little we can do except be ourselves and get on with it.” A range of 'modern Irish' products have emerged from the process as O'Neill believes Irish design is more than the twee and more than the serious, it can also be humorous but well designed. If he succeeds, his endeavours will halve the debt our fair country is currently drowning in. He also sells other merchandise with brilliantly funny Irish slogans like, "Feck It Sure, It's Grand" and "Grand Lovely - Bollox Shite" and "Fine Words Butter No Parsnips".

Erwin Wurms Instructions on how to be politically Incorrect, explores boundaries of privacy and social taboos, the humour is also an astute comment on the atmoshphere of paranoia and invasion of civil rights that is prevalent in the current climate of suicide bombings and terrorist attacks.

In her subversive Sexy Semite (2000–2002), Emily Jacir peppered the Village Voice with personal ads for Palestinians looking to settle down in Israel. One asks "Do you love milk & honey? I’m ready to start a big family in Israel. Still have house keys." Another, more pointed, reads: "You stole the land. May as well take the women! Redhead Palestinian ready to be colonized by your army." The ads slyly suggest a way around an irreconcilable issue in the Middle East peace process: by marrying Israelis, Palestinians can gain citizenship and thus sidestep calls for the "right of return" (an unfulfilled provision of UN Resolution 194 that promises Palestinian refugees the chance to return home). But, given their placement in the love-wanted section instead of world news, the ads seem less about policy than the personal. Individual lives--people seeking love, a sense of home, the kind of daily routine you and I enjoy--are profoundly impacted by the occupation. And perhaps it’s through individual relationships that the conflict can ease. As one ad punned: "Palestinian Male working in a difficult occupation. I’m looking for a Jewish Beauty... Only you can help me find my way Home."

Gender/race stereotyping is another common theme, for example in the confrontational posters by Michael Ray Charles, which expose racial stereotyping by appropriating and exaggerating advertising imagery, and the crawl videos of William Pope L. while Canadian artists Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan create short videos satirizing lesbian and housewife stereotypes.

In Where’s Mickey? (2002), Destiny Deacon analyses issues of race, gender norms and stereotypes through the use of satire, humour, and images we recognise from childhood. Deacon presents us with a bright, colourful image of a "mouseketeer". The Mouseketeers were the youthful fan club of the Disney cartoon characters Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse. These happy, smiling white children were broadcast across America and around the world on the television show The Mickey Mouse Club. This program was broadcast internationally in the late 1950s, a period in history that particularly interests Deacon as it predates many changes to social, race and family relations. Importantly for Deacon the Mouseketeers presented an idealised, sanitised version of what American children should be like. This artwork reminds us of the historical omission of non-white people in the media. By presenting a black Mouseketeer, Deacon corrects this historical discrimination. Questioning identity, its construction and perceptions is integral to Deacon's work. Deacon creates a parody of a female Mouseketeer, (or is it Minnie Mouse herself?) by appropriating parts of the costume (such as the mouse ears hat, shoes and gloves), and by using other found items such as a 1950s style hat. In this photograph Deacon takes this sense of parody further by using a man as the model, further bending and subverting this cultural icon by disrupting our expectations. The image suggests the childish game of dress-ups, with a serious undertone. The bright, flat colours are rather gaudy and cartoonish. The rumpled curtain, shallow stage-like space, and exaggerated pose suggest the theatrical, with the performing figure looking like it is part of a travelling troupe or a vaudeville play. The disembodied leg which can just be seen coming from outside the frame in the bottom left corner further accentuates the feeling of theatricality and artifice.

(from MCA Education Destiny Deacon: Walk & don’t look blak Resource Kit)

Humour is also used to expose cultural or national stereotypes.The Blue Noses Group Chechen Marilyn conflates an image of a female suicide bomber with the pose made famous by Marilyn Monroe in the Seven year Itch. John Carson’s A bottle of stout in every pub in Bundoran, explores the limits and excesses of Irelands drinking culture.“In ritualizing the drinking situation and pointing out the effect of too much alcohol and in depicting all the different types of pubs in Buncrana, my intention is to get people to focus in on and take a considered look at our traditional irish drinking habits. It is then up to the viewer of the work to wonder whether the drinking habit is a valuable cultural heritage, a desirable activity, a futile indulgence, a sinful business or a serious matter for concern.”Refused sponsorship by Guiness who felt it was not in keeping with their policy of moderation.

Christian Jankowski’s The Holy Artwork connect art and religion to the questionable medium of the entertainment industry. Paul Davis Prayer Antennae invites viewers to prostrate themselves in a ridiculous pose in order to insert their heads into a helmet offering communication with god.

In each of these works, the artist's are using humour to play with wider social and political issues, while the medium may have changed, they still bear a moral message rooting them in the tradition of political satire.

However there are artists who use humour on a much more personal level. Paul Davis and Nedko Solakov both use simplistic drawings styles to render comic imagery that confronts their personal fears, as in the collection of illustrations of Solakov’s 99 fears, and Davis’s diagrams of the futility of the daily grind in Wake Up.

Born in 1957 in Cherven Briag, Bulgaria Nedko Solakov lives and works in Sofia. Using a wide range of media and techniques, including painting and the appropriation of found objects, Solakov proposes fictional narratives that are at once humorous and dark.

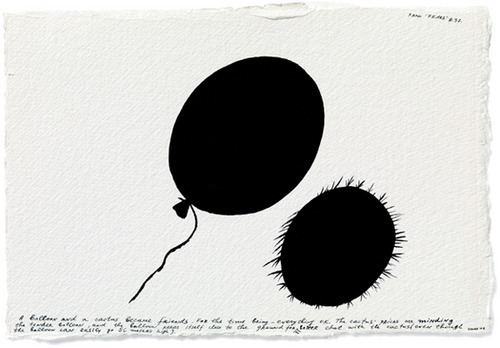

Nedko Solakov, “From ‘Fears’ #37″, caption reads: A balloon and a Cactus became friends. For the time being – everything OK. The cactus’ pricks are minding the tender balloon, and the balloon keeps itself close to the ground for a better chat with the cactus (even though the balloon can easily go 56 meters high).

Nedko Solakov, “From ‘Fears’ #40″, caption reads: “I feel very insecure stepping outside in the darkness”, says the man. “Shut the door! Your light is killing me!” the darkness replies by sending vibes to the man. “This is it – I got goose bumps,” the man mumbles and steps back into the house leaving the door open.